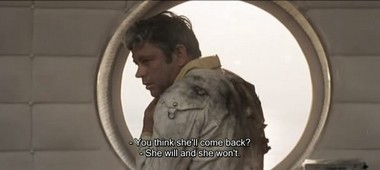

Solyaris (1972) |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

LinksWriting

Art & Design Science Music Film All contributions by Kieran Gosney unless otherwise stated.

© Kieran Gosney and kierangosney.com, 2013. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kieran Gosney and kierangosney.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed