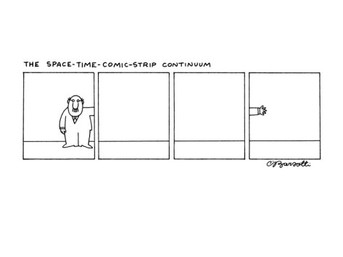

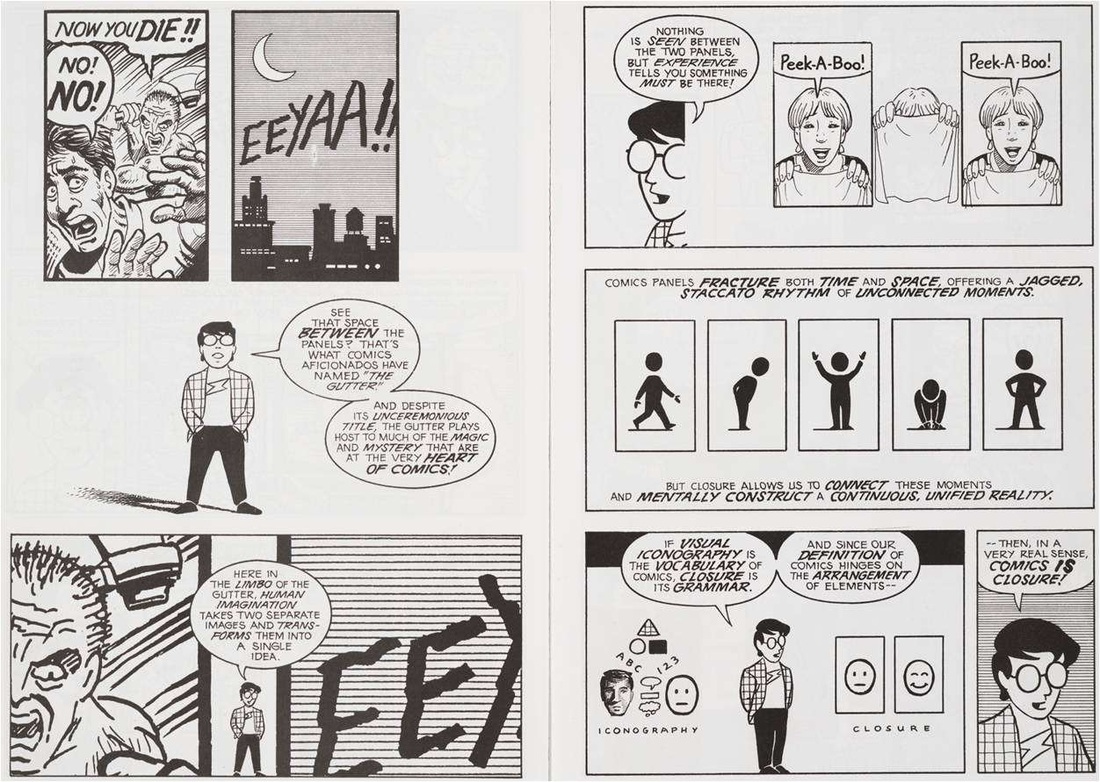

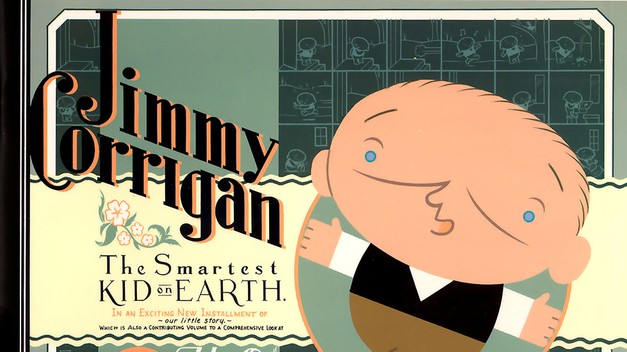

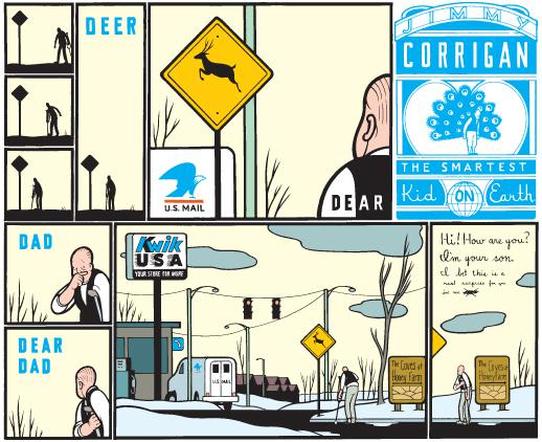

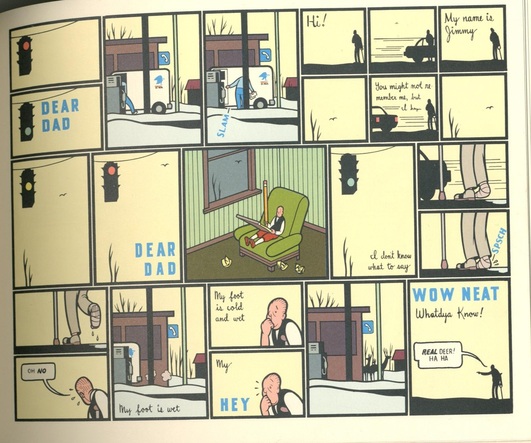

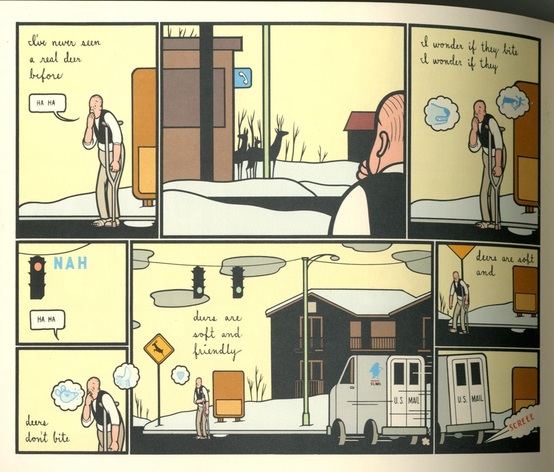

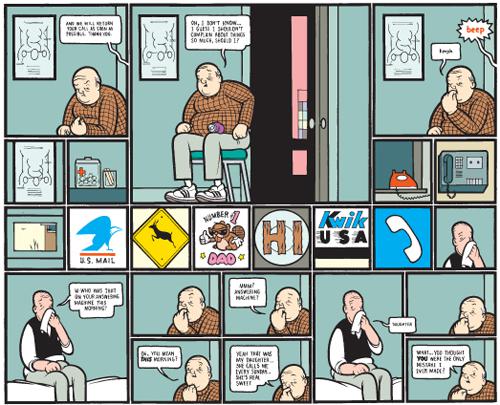

The Space-Time-Comic-Strip Continuum - Charles Barsotti The Space-Time-Comic-Strip Continuum - Charles Barsotti In Michel Gondry’s 2004 film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind the viewer is presented the atemporal perspective of the central character’s actively disintegrating memory. The viewer observes a spatially and temporally fragmented world designed to visualise the errant and subjective nature of memory. The narrative devices employed in the film produce what is arguably one of the most successful representations of the interconnectedness of time, memory and perception in cinema. However, the necessarily linear nature of the film medium creates limitations in how the signification desired by the filmmakers can be delivered. In literature, William Burroughs‘ experimental semi-autobiographical novel Naked Lunch abandoned narrative consistency in favour of thematic continuity, with the aim of a more 'truthful' telling of Burroughs’ subjective experience. The non-linear structure of the novel enables the reader to experience the divided and self-destructive nature of the drug addict and the incoherent form of the novel is a metaphor for the author‘s memories and state of mind. Similarly to Eternal Sunshine, though, the novel may thrash back and forth in time, but the position of the reader follows, in one way or another, the path dug by the narrator. While the reader may skip back and forward themselves to re-evaluate the text, the superposition held by the reader is reliant on the memory of what has been read in conjunction with what is being read in that moment. The sequential art of comic books does not suffer from these same limitations in how it is experienced by the audience. Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics writes: “Unlike other media, in comics, the past is more than just memories for the audience and the future is just more than possibilities! Both past and future are real and visible all around us! Wherever your eyes are focused, that’s now. But at the same time your eyes take in the surrounding landscape of past and future.”  Superman travels to Colonial America through 'a weird mathematical design' Superman travels to Colonial America through 'a weird mathematical design' The past, present and future of the narrative can be displayed simultaneously on a comic book page, enabling authors to exploit the exclusivity of a single image and the intercourse between two or more. The reader ventures back and forward in the story at will, with at least some visual acuity left to the surrounding panels. Although comics do seem, at first glance, to be a simple amalgamation of the graphic arts and prose fiction, this description belies the unique properties of the medium. The sequential art format of the comic offers a unique method of communicating narratives concerning time, memory and perspective. Here I'll look at how just one sequence of pages in Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Boy Kid on Earth by Chris Ware (the greatest comic of all time, if you ask me) performs the impossible of warping the space-time-comic-strip continuum, and what this achieves for narrative and character. In Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan discusses how comics differ from almost all other forms of visual media. "[T]he modern comics strip and comic book," he argues, "provide very little data about any particular moment in time, or aspect in space, of an object. The viewer, or reader, is compelled to participate in completing and interpreting the few hints provided by the bounding lines." McLuhan designated comics “cool” media, an audience-inclusive genre, in that it requires the audience to actively conceive of the sense information which is not provided. This is opposed to film which, designated a form of “hot” media, turns the viewer into “a passive consumer of actions”. The active engagement involved in comic reading that McLuhan is referring to is what Gestalt psychologists call ’the law of closure' - the experience of stimuli, not fully perceived, as a whole. In film, closure between frames operates on a largely subconscious level as our minds fluently connect the independent images into a story of continuous motion. The space in between the sequential images in comic books results in more conscious closure, though, as McCloud explains: “The closure of electronic media is continuous, largely involuntary and virtually imperceptible. But closure in comics is far from continuous and anything but voluntary! Every act committed to paper by the artist is aided and abetted by a silent accomplice. An equal partner in crime known as the reader.” It's this unique control over reader perspective in comics which most benefits the author’s expressed meaning in narratives concerning time, memory and perception. Ware himself speaks to the idiosyncratic associative property of comics: “Unlike prose writing, the process of writing and pictures encourages associations and recollections to accumulate literally 'in front of the eyes;' people, places, and events appear out of nowhere. Doors open into rooms remembered from childhood, faces form into dead relatives, and distant loves appear, almost magically on the page – all deceptively manageable, visceral, the combinations sometime even revelatory. This odd, almost dreamlike characteristic may be somewhat unique to the medium”  As time and space are one and the same in comics, with closure creating narrative in the spaces between panels, and between images and text, meaning can be established, re-evaluated and juxtaposed without the forward push of time’s arrow experienced in literature and film. The “surrounding landscape of past and future” is subject to a reciprocal relationship between author’s intent and the audience’s perception. The intellectual and emotional connection between author and audience forms a strong interaction here. This interaction has to develop, because, as Will Eisner states in his book Comics and Sequential Art, “the artist is evoking images stored in the minds of both parties.” Deer/Dear Dad: Jimmy Corrigan and the Complex Cartoon MindJimmy Corrigan by Chris Ware is a complex narrative, spanning three generations of the Corrigan family, that exploits the huge potential in sequential art for representing memory, perception, subjective experience and expanding narrative meaning. The story concerns the awkward, insular life of Jimmy Corrigan, a “lonely, emotionally-impaired castaway” as Ware describes him, and how it is interrupted by a letter from his estranged father that suggests a meeting. What follows skips back and forward in time, exploring both Jimmy’s childhood and that of his grandfather, delving into how memory and fantasy interact in the mind, often in subconscious ways the significance of which is not immediately apparent. Ware conflates history, memory and fantasy across pages, and within panels, so as to communicate the inner world of the outwardly impassive central character and Ware’s own authorial voice. Leitmotifs, such as a masked superhero and a peach tree, travel from the present subjective perspective into dreams and back again. Historical scenes imprint themselves visually on the present day narrative and ideogrammatic and typographic symbolism operate on several levels at once. All of these narrative devices are often repeated in different contexts to establish new meaning. Examining Ware's work often uncovers several layers of narrative and can be read as a reflection on the graphic novel, its reader, and the process of reading itself. The comic-narrative theorist Gene Kannenberg argues, in his article The Comics of Chris Ware: Text, Image, and Visual Narrative Strategies, that Ware's pages act as "visual-literary totality" whereby text and image, in conjunction with colour, composition and textual layout, operate in a “closed system in which the various elements both act in their traditional representative fashions and, through their spacial juxtaposition, participate in creating larger units of meaning." One section of the book that displays Ware’s creative use of comic narrative to convey and analyse subjective experience begins with the following: Having been startled by an answer phone message from his father’s adopted daughter, Jimmy flees from his father’s house, his mind struggling to deal with the confusing situation. He comes across a road sign, warning of deer in the area, that sparks a stream of consciousness that, on one level, exposes Jimmy's mental state, but on further examination can be read for a wealth of narrative complexity. The closure that occurs throughout these panels creates a realistically mercurial portrait of Jimmy’s confused state of mind, with the reader gleaning meaning from how symbols are established in one context, then reconceptualised when placed in a different context or juxtaposed with something else. The process the reader goes through in evaluating the symbols on the page is similar to the mental process of the character but, at the same time, the reader occupies the omniscient superposition available through the sequential format. For example, our first view of Jimmy is as a silhouette in three panels, the style of which mimics that of the sign Jimmy is reading (fig.1). Here Ware is manipulating the conventional motif of the road sign to highlight how we, as readers, interpret the meaning of the symbolic language of the comic book in a similar fashion to how Jimmy is interpreting the meaning of signs and symbols in his world – as both representative and associative. The ’deer’ sign associating with the mail truck manifests as the form of address ‘dear’ in the beginning of Jimmy’s imaginary response letter to his father, and this conscious formation is visually represented by bisecting the typography (as DE/AR) with the black and white figure of Jimmy in the bottom right of the panel. Following the reader's (and Jimmy's) recontextualisation of the 'deer' sign, Jimmy sees real deer and questions whether he should approach them, concluding that “deers don’t bite…deers are soft and friendly” before being hit by the mail truck (fig.3). Although, in Jimmy’s stream of consciousness, the deer are realised as creatures and the rapidly approaching mail truck is merely an accident waiting to happen, the reader has already reconceptualised the ‘deer’ sign and the mail truck as signifiers of greater meaning. So, when Jimmy steps in front of the truck to the words “deers are soft and…” the reader is considering the implications of Jimmy’s father’s letter and their inability to communicate, and the collision about to occur takes on an ironic thematic significance. This sequence illustrates that meaning and remembrance can be gleaned from the conflation of signs and symbols in human perception of the real world, as it is in comics. In this way, the sequential format and semiotic borrowing serves a narrative function to direct the viewer's gaze through the story, but also a meta-narrative function by visualising Jimmy's subjective experience and exploring thematically the connection between the public language of semiotics and the private of emotional relationships. This connection is further illustrated by Jimmy's stream of consciousness taking on two typographically different forms, those of a handwritten letter and a road sign font. The typography and text placement speaks to the greater thematic meaning of Jimmy's thought pattern. Will Eisner writes, in a comparison between calligraphy and the development of the symbolic language of comics, that “letters of the alphabet when written in a singular style, contribute to meaning....this is not unlike the spoken word, which is affected by the changes of inflection and sound level.” Ware takes advantage more than most comics writers of the possibilities in what Charles Hatfield in Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature called a “collapse [of] the word/image dichotomy” inherent in comics, whereby images can work like text and text can work like images. By using the road sign typography to embolden the text “DEAR DAD”, Ware tells the reader that, to Jimmy, the thought of communicating emotionally with his father is a powerful controlling force in his mind, like the controlling force of the traffic sign. The “DEAR DAD” image is first seen directly opposite the handwritten letter construction, with both emotionally weighted typographic images approaching one another as they surround the stylistically different and centrally placed, therefore attention vortexing, panel of Jimmy struggling to write his letter, having shrunk to an infantile form (fig.2). The anxiety of communication with his father is now confronting his staccato emotional language to push him into a state of childlike helplessness. As Jimmy concludes that “he doesn't know what to say”, he is surprised by a car and steps backwards into a puddle, remarking (in the handwritten typography) that “his foot is wet” before being surprised a second time by the appearance of real deer that, it is important to note, appear beneath another symbol of communication, the telephone (fig.3). With the interruption of real traffic and the appearance of real deer, the semiotic signification of the road signs become concrete, and Jimmy's typographically different thoughts meet inside a panel for the first time. The road sign typography is now an exclamation of joy, in unison with the handwriting, at the beautiful reality of what signs and symbols can represent. We can see the mail truck coming, however, and know that 'deers/dears' can “bite”, and that Jimmy cannot escape the significance of certain symbolic relationships already established. All of the important signs and symbols of this section of the book are repeated, with several other signs, at later points in the book, such as this awkward scene between Jimmy and his father in a clinic after the mail truck collision: The central belt of symbols act to visually articulate the summation of Jimmy's relationship with his father in the semiotic language that Ware presents as intrinsic to modern life (fig.4). Ware is adapting the post-modern semiotic argument that the language-dominated culture is moving towards the dominance of the iconic, to communicate the microscopic isolation of Jimmy while maintaining a macroscopic perspective on modern life. In both the above and the previous sequence, Jimmy takes the symbolic associations and reconfigures them in an attempt to conquer his emotional inarticulation. Readers are invited to construct a meta-narrative through the directed, but also free-, association of symbols across the information-dense comics grid, as well as through the sequential panel narrative. In both contexts, the usually dispassionate semiotic system of road signs and symbols become an emotional language that relates as much to the narrative of this scene as it does to the expansive thematic concerns of memory, sense of identity and self-image in our semiotically-cluttered modern world.

For Ware and others in his field, the comic medium is intrinsic to the narrative. Both Eisner and Ware use the comics medium to create works that communicate meaning in ways that only sequential art can. In Jimmy Corrigan, the 'inclusive gestalt' that McLuhan talked about provides the ideogrammatic language of comics the means to put the reader in a supra-narrative position more connected to what McLuhan calls the “total field of awareness that exists in any moment of conciousness.” By exploiting the way that complex narratives can be built with the audience participation inherent in closure mechanics, artists like Ware establish themselves as germinal storytellers who can expand the language of comics and the possibilities of narrative in general. By Kieran Gosney Further Reading and Links: Scott McCloud examines comics by making comics The fantastic documentary Will Eisner: Portrait of a Sequential Artist. Here's a clip. Chris Ware and comics-journalist Joe Sacco discuss their work and the medium here, for the 2013 Edinburgh Book Festival. A collection of all things Chris Ware at the Acme Novelty Archive. This American Life episode on comics and superheroes here. They also did a comic on how to make radio stories that you can find here. State of the Re:Union also has an episode devoted to comics. There's a particularly moving story here about how the idea of Superman leads hundreds of strangers to help a mentally troubled Superman memorabilia collector after he is robbed. "I feel that people understand me now, for the first time in my life," your heart will melt. The Comics Grid The Beat, daily dose of comics news and reviews The Comics Journal is your place for the more underground or alternative comics Gosh! is London's best comics shop and they have a great blog here Some great comics that you might not have read: Asterios Polyp by David Mazzucchelli After Jimmy Corrigan, my second favourite comic. Who'd of thought the story of a pretentious, miserablist professor of architecture could be so moving and entertaining. Features some of the most breathtaking comic art ever put to page. Equally concerned with, and self-aware of, the medium of comics and graphic design as Ware, Mazzucchelli has a lot to say about aesthetics, relationships and metaphysics. Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea by Guy Delisle Behind the iron veil of North Korea. Delisle spent two months living in North Korea and his experiences form the basis of this amazing comic. A unique slice of life. Logicomix: An Epic Search For Truth by Apostolos Doxiadis, Christos Papadimitriou with art by Alecos Papadatos and Annie Di Donna The story of Betrand Russell and the search for absolute truth. Like Asterios Polyp, Logicomix is interested in the grandly philosophical as well as the personally meaningful. A comic that makes maths interesting to everyone is not something to be sniffed at. John Wilcock, New York Years by Ethan Persoff & Steve Marshall Online comic book about the 1960's underground publisher John Wilcock, one of the co-founders of the Village Voice. A real behind the scenes look at publishing and the American counter-culture. Makes most internet comics look like juvenile sketches. 3bute African graphic journalism with crowd-sourced content. The future of comics journalism? It's certainly got the potential to be revolutionary. Happydale: Devils In The Desert by Andrew Dabb and Seth Fisher A trio of varying criminal debauchery find themselves in the strange town of Happydale, populated by the weird, the deformed and the outcast. Two issue prestige from DC's Vertigo imprint. Beg The Question by Bob Fingerman Graphic novel reworking of Fingerman's Minimum Wage series. Such a painfully accurate representation of the ordinary troubles in life and relationships that it can be hard to read. It helps that it is also very funny. Fingerman also wrote White Like She, in which a middle-aged black man's brain is transplanted into a white teenage girl. Yep. You want to read that.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

LinksWriting

Art & Design Science Music Film All contributions by Kieran Gosney unless otherwise stated.

© Kieran Gosney and kierangosney.com, 2013. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kieran Gosney and kierangosney.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed