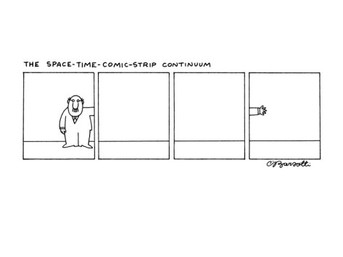

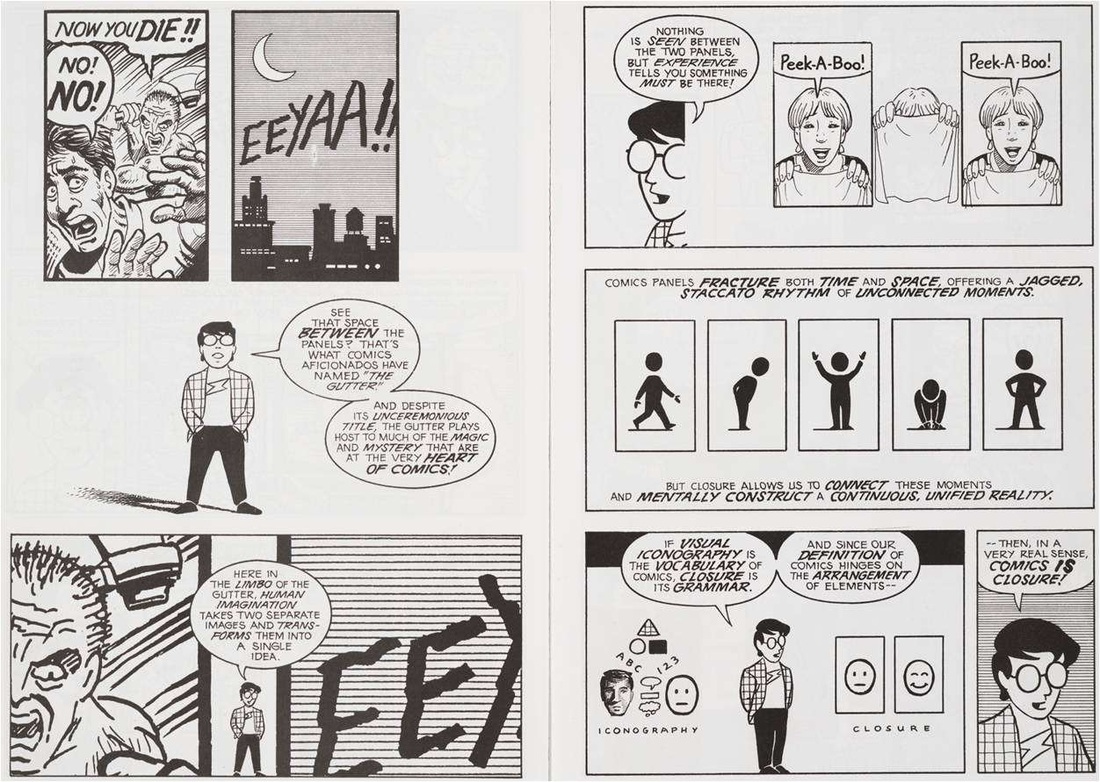

The Space-Time-Comic-Strip Continuum - Charles Barsotti The Space-Time-Comic-Strip Continuum - Charles Barsotti In Michel Gondry’s 2004 film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind the viewer is presented the atemporal perspective of the central character’s actively disintegrating memory. The viewer observes a spatially and temporally fragmented world designed to visualise the errant and subjective nature of memory. The narrative devices employed in the film produce what is arguably one of the most successful representations of the interconnectedness of time, memory and perception in cinema. However, the necessarily linear nature of the film medium creates limitations in how the signification desired by the filmmakers can be delivered. In literature, William Burroughs‘ experimental semi-autobiographical novel Naked Lunch abandoned narrative consistency in favour of thematic continuity, with the aim of a more 'truthful' telling of Burroughs’ subjective experience. The non-linear structure of the novel enables the reader to experience the divided and self-destructive nature of the drug addict and the incoherent form of the novel is a metaphor for the author‘s memories and state of mind. Similarly to Eternal Sunshine, though, the novel may thrash back and forth in time, but the position of the reader follows, in one way or another, the path dug by the narrator. While the reader may skip back and forward themselves to re-evaluate the text, the superposition held by the reader is reliant on the memory of what has been read in conjunction with what is being read in that moment. The sequential art of comic books does not suffer from these same limitations in how it is experienced by the audience. Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics writes: “Unlike other media, in comics, the past is more than just memories for the audience and the future is just more than possibilities! Both past and future are real and visible all around us! Wherever your eyes are focused, that’s now. But at the same time your eyes take in the surrounding landscape of past and future.”  Superman travels to Colonial America through 'a weird mathematical design' Superman travels to Colonial America through 'a weird mathematical design' The past, present and future of the narrative can be displayed simultaneously on a comic book page, enabling authors to exploit the exclusivity of a single image and the intercourse between two or more. The reader ventures back and forward in the story at will, with at least some visual acuity left to the surrounding panels. Although comics do seem, at first glance, to be a simple amalgamation of the graphic arts and prose fiction, this description belies the unique properties of the medium. The sequential art format of the comic offers a unique method of communicating narratives concerning time, memory and perspective. Here I'll look at how just one sequence of pages in Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Boy Kid on Earth by Chris Ware (the greatest comic of all time, if you ask me) performs the impossible of warping the space-time-comic-strip continuum, and what this achieves for narrative and character. In Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan discusses how comics differ from almost all other forms of visual media. "[T]he modern comics strip and comic book," he argues, "provide very little data about any particular moment in time, or aspect in space, of an object. The viewer, or reader, is compelled to participate in completing and interpreting the few hints provided by the bounding lines." McLuhan designated comics “cool” media, an audience-inclusive genre, in that it requires the audience to actively conceive of the sense information which is not provided. This is opposed to film which, designated a form of “hot” media, turns the viewer into “a passive consumer of actions”. The active engagement involved in comic reading that McLuhan is referring to is what Gestalt psychologists call ’the law of closure' - the experience of stimuli, not fully perceived, as a whole. In film, closure between frames operates on a largely subconscious level as our minds fluently connect the independent images into a story of continuous motion. The space in between the sequential images in comic books results in more conscious closure, though, as McCloud explains: “The closure of electronic media is continuous, largely involuntary and virtually imperceptible. But closure in comics is far from continuous and anything but voluntary! Every act committed to paper by the artist is aided and abetted by a silent accomplice. An equal partner in crime known as the reader.”

0 Comments

|

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

LinksWriting

Art & Design Science Music Film All contributions by Kieran Gosney unless otherwise stated.

© Kieran Gosney and kierangosney.com, 2013. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kieran Gosney and kierangosney.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed