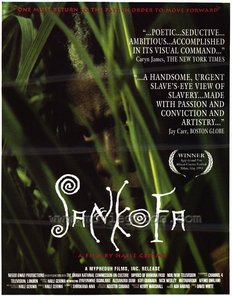

Scotland's Africa in Motion film festival has just finished so I thought I'd write about the African sci-fi and fantasy cinema that is of particular interest to me.  Pumzi, written and directed by Wanuri Kahiu Pumzi, written and directed by Wanuri Kahiu Afrofuturism is an aesthetic born of the African diaspora and found in afro-centric visual art, music and literature. The aesthetic unites science fiction, historical and alternate-history fiction, magic realism, fantasy, and African myths in the context of 20th-century technoculture. Originating in the music and persona of Sun Ra, but defined by Mark Dery in his 1995 essay Black to the Future, the Afrofuturist aesthetic foregrounds Black agency and creativity. Sandra Jackson and Julie Moody-Freeman, in The Black Imagination and the Genres, define the core principle of Afrofuturist fiction as: “Imagined futures in which African descendant people as well as other people of color are neither conspicuously absent nor marginalized as background or expendable characters, but…instead not only present but rather active agents—protagonists and heroes—in events which take place here on the planet Earth or elsewhere in the universe, set in the past, alternative pasts, distant and near future times”. Although conceived outside of Africa by Afro-Americans, Afrofuturism has a proven reflexive relationship with the old continent. The separation between the speculative fictions of the diaspora and native Africans is less distinct that in the 1950's, when Afrofuturism was born. Looking at African speculative fiction and fantasy cinema through the scope of Afrofuturism connects the geographical separation from heritage felt by the Afro-American artists to the dehistoricisation and cultural alienation inflicted on native Africans by colonial oppressors. The artist and writer Tegan Bristow, in her article We want the funk: What is Afrofuturism to the situation of digital arts in Africa?, published in the journal Technoetic Arts, considered how the ideas developed through Afrofuturism are being explored in contemporary African arts. Often this development is discussed alongside the unique use of communications technology by Africans, such as the Kenyan phone banking system or BRCK. Although often dismissed as technologically backwards, and therefore unable to express the same speculative fascination with technology as the West, Africa defies simple stereotypes and is producing great science fiction and fantasy art, from an African perspective. Afrofuturism is now more than just an American aesthetic, being taken up by Africans and becoming a more global celebration of Black culture.  Sankofa (1993), written and directed by Ethiopian film-maker Haile Gerima, concerns an Afro-American model's mystical transportation to a West Indian plantation, where she experiences chattel slavery first hand. This African-produced fantasy film, dealing with Maafa and the African diaspora, can be seen as a pioneer in connecting the Afrofuturism of the African diaspora with that of native Africa. Africa Paradis is a French-Beninese co-production about a future in which Africa is entering a period of great prosperity while Europe suffers a massive economic downturn, leading to large-scale illegal immigration of Europeans into Africa. The satirical commentary is sharp and, now that many African countries are in the ascendant and Europe struggles under austerity with limited growth, it only proves itself to be more keenly observed as time goes on. Watch the trailer here. Produced more recently, Pumzi, written and directed by Wanuri Kahiu, is Kenya's first science-fiction short film and was released to great success both inside and out of Africa, subsequently winning the 2010 Cannes Best Short Film. The film, about a female ecologist's journey to regenerate life in a post-apocalyptic desert outside of a repressive subterranean city-state, uses the power of speculative fiction to comment on the present, and demonstrate a possible future. Pumzi's narrative counters marginal representation of women in African 'malestream', the image of African women as inferior and subordinate, the Western view of Africa as technologically ignorant, and promotes ecological awareness. Pumzi joins Les Saignantes (Bekolo, 2005), Africa Paradis (Amoussou, 2006) and Kajola (Akinmolayan, 2010) as the cinematic side of Africa's postmillennial Afrofuturist expression. I recommend you watch Wanuri Kahiu's Pumzi here.  Kudzani Moswela as Asha in Pumzi Kudzani Moswela as Asha in Pumzi Kahiu's newest film project, due for release in the summer of 2013, is an adaptation of the Nigerian-American writer Nnedi Okorafor's World Fantasy Award winning novel Who Fears Death. Set in a post-apocalyptic Africa, the story concerns a woman of the Okeke, a tribe enslaved by the dominant Nuru, who gives birth to a child conceived through rape by a Nuru general. Walking into the desert to die, the woman instead gives birth to a baby girl with hair and skin the colour of sand and names her Onyesonwu, which means 'who fears death' in an ancient tongue. As the girl grows, a victim of oppression in her village as both a woman and a child of rape, she displays miraculous powers such as shapeshifting and travel into the spiritual world, which she uses to confront her father and free her enslaved people. Onyesonwu's birthright and colouring alludes to the Sudanese Janjaweed's use of rape as a weapon to give birth to lighter skinned children. Children of rape victims are looked down upon in Darfur communities out of fear that the children will become Janjaweed, with lighter skin and softer hair giving away ethnicity. The story is also a condemnation of culturally ingrained oppression of women and brutal rites like female circumcision, as well as the destruction of culture, language and religion caused by the African slave trade. Much like how Philip K. Dick's work is celebrated as trenchant commentary when viewed through the prism of counter-culture collapse in post-modern America, African works of quality should enjoy the same reflection and appraisal vis-à-vis Africa's technological and social concerns. In a TEDx talk, given in Nairobi in July, Kahiu references Dogon ancient astronaut mythology and Ngoma philosophy to demonstrate a historical basis for the Afrofuturist aesthetic in Africa and provides examples of artists, such as the Kenyan music group and art collective Just a Band, who put Afrofuturism in the context of Africa. Kahiu concludes that Africans "can't reclaim history" but based on the conceptual framework of Afrofuturism as defined by Mark Dery, "we can project our future."

In the article 'Is Africa Ready For Science Fiction?' by Nigerian-American sci-fi writer Nnedi Wahala, Wahala states that: “There is a weird divide and connection between the technologically advanced and the ancient. For example: People will have cells phones in rural villages yet have no plumbing or electricity or one will opt to buy a laptop instead of a desktop computer because a laptop has its own power supply, most useful for when 'NEPA takes the lights.'" As well as a lack of research into, and media attention for, African sci-fi and fantasy, there is limited ground-level documentation of the film industries, outside of South Africa, and the development of intra-African funding networks. Documentaries such as Welcome to Nollywood by Jamie Meltzer and Franco Sacchi's This Is Nollywood are two examples in this small domain. Particularly relevant to Nigeria's Nollywood, reported by UNESCO in 2006 as the second most prolific national film industry in the world, is how a cinematic genre that deals with future worlds and technology, as well as the wildly fantastical, matures within the strictures of relatively minuscule budgets, little state support and a scarcity of advanced film equipment and training. Nigeria has reacted quickly to the future of moving image distribution, and its film industry's dependence upon digital film-making and distribution relates well to Nnedi Wahala's comments above. In Nigeria alone, there are a number of burgeoning Afrofuturist projects following in the footsteps of Niyi Akinmolayan's Kajola (2010) that share a similar goal of promoting cinema that explores contemporary black African issues through speculative fiction. Go to Youtube and you'll find many zero-budget Nigerian sci-fi and fantasy films. Not only is Africa ready for science fiction, and has been for some time, but Africa's 'weird divide and connection' is a breeding ground for a unique direction in speculative and fantastical fiction. A repatriation of pan-African Afrofuturism heralds the birth of an exciting new cinema. Perceptions of the future, and fantastical realms, say a lot about the present and the ordinary, and an examination of African sci-fi and fantasy is a great way to understand modern Africa, where it's going, and where it's been. By Kieran Gosney Links and further reading:Watch Wanuri Kahiu's fantastic short film Pumzi here An interview with Kahiu for Bitch Magazine here AfroCyberPunk: Exploring the Future of Africa is a great website devoted to Africa Sci-Fi Mahala is a free South African magazine on African arts and culture Superpower: Africa in Science Fiction exhibition that was held at Arnolfini in Bristol. Audio of Lizelle Bisschoff, professor of Contemporary African Cinema at the University of Edinburgh, discussing the exhibition here. Exhibition curators Nav Haq and Al Cameron discuss ideas relating to Africa in science fiction with exhibiting artist Mark Aerial Waller here. Mark Sinker reviews the exhibition for BFI here. 3bute is a new form of internet journalism; immersive and democratic. Illustrated non-fiction stories from all over Africa, which can then be tagged with crowdsourced content. Afrofuture exhibition at the 2013 Milan Design Week Check out some great African music: Just A Band, Spoek Mathambo, DOOKOOM, and The Brother Moves On. And finally, check out the incredible Mausoleum of Agostinho Neto in Luanda, Angola, the finest example of futuristic architecture in Africa.

1 Comment

|

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

LinksWriting

Art & Design Science Music Film All contributions by Kieran Gosney unless otherwise stated.

© Kieran Gosney and kierangosney.com, 2013. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kieran Gosney and kierangosney.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed